Weakness is Strength (…until it isn’t)

What is power—what is empire—today?

What does it mean to be at the centre of the international system?

What makes America the global hegemon?

Focusing on Trump and his tariffs, we might narrow the question: when we look at the huge volume of foreign goods the U.S. imports, the trade deficit with the rest of the world that the Trump administration wants to curb—is this a wound bleeding an emperor dry, or is it the tribute he receives from his vassals?

The answer is both.

The dollars America pays foreign countries to buy and import their goods is, it turns out, largely invested back into America: the dollar is a stable asset for foreign businesses and central banks to own. They make money exporting to the US, and they use that money to purchase U.S. debt, which makes Wall Street the force that it is, and allows Washington its massive budgets.

At least that’s one plausible account.

But this also means that a rift opens up between the dollar (which foreign investors want to keep strong) and the real economy, domestic U.S. production (which withers away—atrophies as reliance on foreign imports becomes entrenched with every passing decade).

The dynamic here is that of the so-called Triffin dilemma, and is what ex-Finance Minister for Greece Yanis Varoufakis calls the Global Minotaur.

The dollar stays strong, the real economy gets weak.

But why should that matter?

If trade deficits allow U.S. finance to conjure up the formidable storms of capital that it does, and a strong dollar causes the world to bow and huddle under it as reserve currency, is the gap between the country’s currency and productivity not just the price of power—the necessary wages of empire?

Yes.

But like a master growing lazy, empires can die of success.

“Financial Gnosticism”

It’s become a meme to say the (post-)modern Left is “gnostic,” meaning that, like some early Christian heresies, it wants to escape the physical world, it divorces mind from body (gender isn’t biological, it’s an identity; nations aren’t defined by a group whose generational effort went into building them up, they’re legal contracts. That sort of thing.)

But the “gnostic” —or, better, world-denying—label applies just as well to American geopolitics.

Rending apart mind and body is analogous to divorcing the world of currency, abstract value, from real production and jobs. All empires tend to turn on their core demographic. Political elites come to see their interests as global, disconnected from place and people (I’ve made videos about that before). Today, this manifests in financialization and de-industrialization.

Of course, as the body is allowed to wither, the mind will as well, and de-industrialization means two things: social vulnerability and strategic vulnerability.

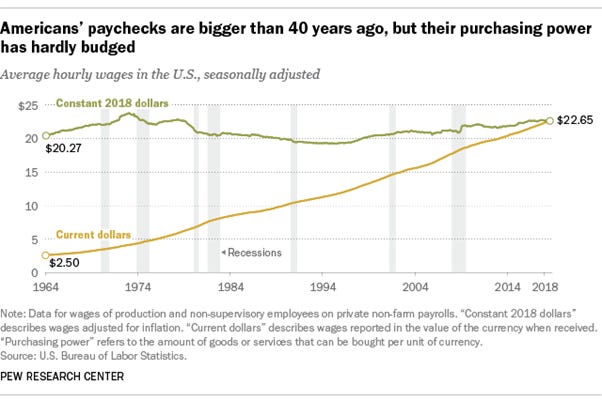

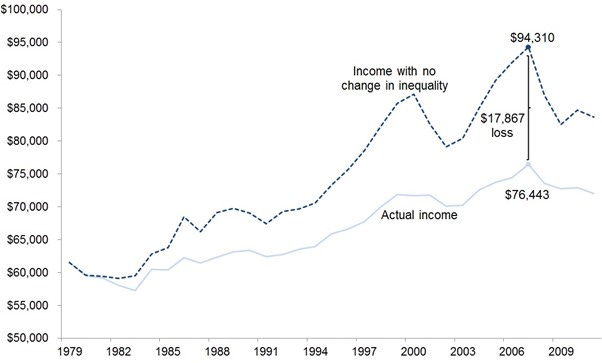

On the social side, simmering dissatisfaction due to loss of purchasing power (and especially the sense of relative deprivation compared to how things were even one generation back) resulting from hollowed out manufacturing could escalate and threaten the political order.

In terms of strategic vulnerability, reliance on off-shore, scattered supply chains in key strategic sectors becomes a problem when rising powers like China threaten to overtake the U.S. VP JD Vance has flagged this as a concern for the administration:

“China…makes more commercial ships than the rest of the world combined. In fact, one of Beijing’s state-owned firms built more commercial ships just last year [2024] than all of America has produced since the end of World War II.”

Dollar Devaluation

Trump’s tariffs are meant to get countries to agree to stop hoarding dollars and let their own currencies appreciate, since a stronger home currency lowers the local cost of imported inputs and cushions tariff impacts. If central banks slow their purchases of U.S. bonds—or begin to sell in order to stem tariff-related losses—this would result in a drop in dollar demand.

But the White House is shooting for a partial devaluation only: recalibrating global currency markets enough to increase export competitiveness, but not enough to dethrone the dollar (or at least not enough to open it up to serious competition, as the dollar’s status proper would be difficult to usurp entirely, see the so-called “Eurodollar”). This might be partly achievable by getting countries to sell U.S. debt while not buying other currencies that compete with the dollar. Rather, Trump likely wants them to buy assets the U.S. holds, like Stablecoins.

That would be the aim of bilateral tariff negotiations. A future “Mar-a-Lago accord” would need to define this, just as the December 1971 Smithsonian agreement under Nixon, and later 1985 Plaza Accord, define the post-Bretton Woods system we’ve lived under for decades.

The Nixon Precedent

Indeed, in August of 1971 President Richard Nixon did basically the same thing as Trump is attempting. The so-called “Nixon Shock” imposed a 10% tariff on allies and resulted in an agreement by December (we can be confident that Scott Bessent, if not Peter Navarro, is looking to Nixon, even in terms of the 90-day negotiation period).

“The dollar is our currency, but it’s your problem.”

So said U.S. Treasury Secretary for Nixon, John Connally, to European Finance Ministers at the 1971 G10 meeting in Rome.

We could equally reverse the aphorism,

“The dollar is your currency (the world’s reserve currency), but it’s our (the American people’s) problem.”

Devaluing the dollar was necessary. Its value had to float with respect to other currencies, free of Bretton Woods’ fixed currency exchange rates (and also with respect to the value of gold, since Nixon ended the Gold Standard).

Nixon called the December Smithsonian agreement “the most significant monetary agreement in the history of the world.” The depreciation of the dollar against OECD currencies had reached just under 8% (or 12% excluding Canada). Paul Volcker, who was Under Secretary for International Monetary Affairs at the time, however, was not impressed. He later wrote that

“It was well short of what we felt we needed to restore a solid equilibrium in our external payments…But the stonewalling of the [European] Common Market and Japan had been effective….”

In 1978, now as President of the Federal Reserve Bank in New York, Volcker, explained that the United States had moved to effect a “controlled disintegration of the world economy.”

Political Power isn’t Purchasing Power

Radical as this might have seemed, it marked a policy direction later administrations stuck to. Import levies remained a tool in the policy arsenal of later administrations. In the 1980s, Treasury Secretary James A. Baker III, got President Reagan and Volcker to formalize the currency realignment further with the Plaza Accord, in which major economies agreed to jointly intervene in currency markets to depreciate the dollar.

But for all that, Nixon’s Smithsonian Agreement and Reagan’s Plaza Accord were followed by relative wage stagnation for most Americans, especially between the 1970s and 2010s, as well as growing inequality.

That’s an important lesson from history.

Raising wages requires pressure and policy: Pressure from the people, policy from government. If there is no political will to distribute the tariff-induced influx of capital among the U.S. workforce, it simply won’t happen.

And Trump, for his part, hasn’t rolled out a robust industrial policy to properly channel returning capital. What he’s suggesting in its place are corporate tax cuts and the like. He also doesn’t seem to have incentives or legislation in the works to keep companies coming into a tariff windfall from succumbing to shareholder pressure and simply distributing that windfall through stock buybacks and dividends, instead of investing it in expanding domestic production with all the rapidity and urgency demanded by the hit to American purchasing power.

Finance is parasitic on the economy in America, and this would need addressing. Without that piece of the policy puzzle, economic treason, so to speak, will thwart otherwise good trade deals.

Automation Nation, Immigration Nation

In fact, apart from the precedent of salary stagnation and the lack of policy to accompany the tariffs, today’s America faces the problem of automation: it is possible to succeed in onshoring manufacturing without getting significant job creation.

Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick has all but admitted the point, speaking of the creation of “great jobs of the future,” he cited robot maintenance. Of course, we know there are always more robots than engineers. The manufacturing that tariff negotiations will onshore are going to come largely from sectors that don’t require a large local workforce. They need persons skilled in overseeing automated systems rather than traditional assembly line labour.

JD Vance echoed this,

“We will always centre American workers in our AI policy. We refuse to view AI as a purely disruptive technology that will inevitably automate away our labour force. We believe and we will fight for policies that ensure that AI is going to make our workers more productive, and we expect that they will reap the rewards with higher wages, better benefits, and safer and more prosperous communities.”

It’s a nice sentiment (we certainly shouldn’t pine for a return of factory jobs without the ease made possible by AI). But it’s also unrealistic absent very clear favourable legislation and industrial policy—some vision for how the majority will see its purchasing power increased by a boost to national competitiveness.

Concretely, we have the example of Apple’s U.S. Mac Pro production.

Since 2013, Apple has been assembling the Mac Pro in Austin. Previous efforts at re-shoring by Apple, like a $390 million investment in Finisar back in 2018, also created little employment—about 500 jobs in Sherman, Texas. Indeed, Apple’s manufacturing presence in the state remains small (for which reason Trump recently threatened a 25% tariff on Apple’s iPhones produced outside the US).

And yet, Apple is supposed to be one of the principal champions of a future return of U.S. manufacturing. In 2025, the company announced a $500 billion investment over four years, including a 250,000-square-foot server plant in Houston with Foxconn, set to open in 2026. Of course, even on paper, most of the 20,000 new roles in the plan are expected to be in R&D.

And apart from automation, there’s immigration.

Even the engineering and supervisory jobs onshoring will create may not go to natives. In 2024, Trump said he wants immigrants to feed the AI boom, and he reiterated this during the controversy around expanding the H1B Visa program:

“We’re going to let a lot of people come in because we need more people, especially with AI coming…and the farmers need [people], everyone needs people.”

Automation is unavoidable, but limiting immigration and training Americans to be engineers and robot-overseers makes sense, albeit those Americans will charge more than H1B holders and the like. Of course, that’s a good thing. In fact, more needs to be done to distribute post-tariff returning capital among the workforce in order to increase purchasing power, which is a problem for all developed economies in the age of AI.

“Strategic De-Coupling”

We got another 90-day negotiation after the May 12th US-Chine agreement in Geneva, during which the U.S. pulled its 145% tariffs down to 30%, with China reciprocating by scaling-down from 125% to 10%. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent explained the aim of the subsequent negotiations:

“We do not want a generalized decoupling from China. But what we do want is a decoupling for strategic necessities, which we were unable to obtain during Covid. We realized that efficient supply chains were not resilient supply chains.”

The initial pretension of re-negotiating U.S. hegemony proved too tall an order. Liberation Day forced China to show its teeth: exports rose to 8.1% year-over-year in April (surpassing projections of 2%). Goldman Sachs has now revised its economic forecast for China to 4.6% GDP growth for 2025 compared to 4%. The current 90-day tariff reduction may likewise stimulate Chinese manufacturing, and shipping demand has risen, with freight businesses seeing an increase in port traffic as companies move to deliver ahead of the end of the tariff pause (although ultimately decoupling from the U.S. will slow Chinese growth).

In any case, the real impetus behind Liberation Day, namely the need to onshore strategic sectors (“steel…critical medicines, semiconductors”) remains. That’s the irony: on-shoring to avoid future vulnerability and collapse also galvanizes China; avoiding the end of U.S. power means precipitating the end of unipolarity and the rise of bi-polarity. Great power competition never ceased; US-Chinese mutual interest in decoupling means coming to an understanding on the terms of economic conflict.

(For conflict it will remain—after Geneva, Washington apparently warned its companies not to use Huawei AI chips, prompting China’s Commerce Ministry to complain that the U.S. was “abusing export controls to suppress and contain China.”)

Beyond this, Bessent’s casual swapping out of “efficient supply chains” as the central aim of trade relations for resiliency is a shift away from the ethos that has long dominated, a retreat from globalisation.

Wallstreet and permanent Washington might have continued pursuing their interests in global terms, detached from American soil—were it not that the rise of China threatened (as did the MAGA base).

No Return to U.S. Hegemony

If we return to the Nixon parallel, there is far more scope for America’s trade partners to turn to China today than there was for liberal democracies to pivot towards the Soviet Union in the 1970s or 1980s.

In 1970, the USSR’s GDP was $433 billion compared with the US’ $1.1 trillion—about a third. In 2024, China’s (nominal) GDP was about $19 trillion compared to $28 trillion for the US, so over half.

In 2023, China represented 14.2% of global merchandise exports—making it the world’s top exporter—while the Soviet share of trade in 1970 was far lower, and its export sector far more limited to its own Comecon spere.

The stark contrast between the two eras means that Trump should be careful with his vassal states, because they do have options, taking care to project competence and certainty. Competence would mean not including uninhabited territories in the original Liberation Day list, nor countries whose trade imbalance with the U.S. is structural (they’re too poor to buy American goods) and who provide the U.S. with resources it does not want to, or cannot, produce itself (like diamonds from Lesotho). Instead, tariffs should have signalled strategic supply chains.

As for certainty, the U.S. retreated rather quickly from its initial tariffs, but, perhaps more importantly, its various early concessions, including exempting Chinese electronics from tariffs, give the impression of an improvised, rather unconvincing, brinkmanship.

As a result, we’re going to see not a return to American unipolarity, but US-China bi-polarity emerging into clear relief.

To close off, what is good about the Trump administration is the recognition of certain structural changes: economic and geopolitical fundamentals are forcing a retreat from the excessive divorce between currency and actual productive capacity. Vance’s talk of AI not costing jobs and Bessent emphasising resilience over cost-efficiency in trade, for example, are great. The problem is the lack of real policy to ensure this comes to good port (for the American worker, not least).

Just as Trump’s “America First” foreign policy is hopelessly saddled by inherited subservience to Israel, so too his economic vision is rather half-hearted.